A Third Way Between Relief and Development

In the humanitarian and development sector, there has been a very long history of applying relief methods in situations where communities are stable and can invest in development initiatives. From a humanitarian point of view, it’s natural to want to feed the hungry and clothe people who need it. It’s a compassionate response. However, prolonged humanitarian aid can lead to a sense of learned helplessness and further exacerbate dependency on aid, as a one-way giver-beneficiary model can undermine local people’s ability to procure their own solutions.

On the other hand, some staunch development professionals are vehemently opposed to offering any aid whatsoever. I’ve read case studies of leaders of organizations who have completely halted operations in developing nations because they were not 100% sustained by local people.

Indeed there are times when it’s appropriate to provide aid, such as during war, or after a natural disaster for example. Generally it’s appropriate in situations where people are truly unable to provide for themselves. In my opinion, a good rule of thumb to follow when discerning if relief or development is the best measure is to ask: if one is doing for another what the other could do for him or herself for a prolonged period of time, the method should be re-evaluated.

One organization that has done a phenomenal job of bridging the gap between relief and development is Rise Against Hunger. Their model targets “last-mile communities within hunger pockets designated ‘serious’ or higher on the Global Hunger Index, which are the hardest places to reach and are often difficult to access, lack communication and have poor infrastructure.” Rise Against Hunger facilitates locally-led development by working in collaboration with global impact partners to train local communities on climate-resilient agricultural practices and how to grow a surplus of produce that community members can take to market and generate income. They understand that agricultural development takes time to cultivate, so they offer a “safety net” program by providing highly nutritious meals to schools and communities while they are implementing food-smart agricultural practices.

Bryan Pride, who serves as the Technical Program Director at Rise Against Hunger, has seen first hand the transformation that this model can make on communities to ensure they are not only food secure, but also have access to proper and diverse nutrition. While addressing food insecurity is crucial, Mr. Pride has also affirmed that food security programs must also ensure that food cultivated is nutritionally diverse to ensure communities not only are adequately fed, but also are provided essential nutrients to thrive.

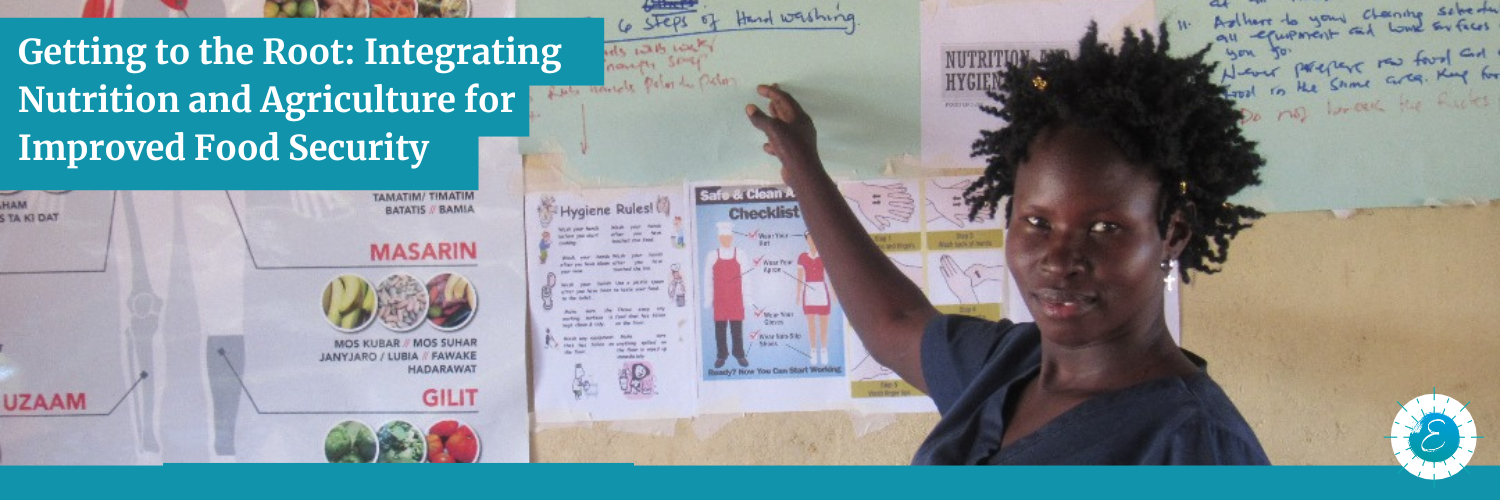

Mr. Pride and his colleague Chelsie Azevedo, who serves as the Nutrition Technical Advisor for Rise Against Hunger, drafted a white paper entitled: Getting to the Root: Integrating Nutrition and Agriculture for Improved Food Security. They share insights on the importance of integrating nutrition and agriculture concepts in food security programs, and offer suggestions on how to integrate both aspects at the community level to ensure a holistic and resident program.

Their white paper provides a very thorough analysis of not only the why for integrating nutrition and agriculture, but insightful examples for how NGO practitioners can empower people with practical knowledge and skill sharing. Their analysis and examples came from direct field experiences with partners in Mali and South Sudan.